Mental accounts and expectations (Tversky and Kahneman, 1981)

• Imagine that you have decided to see a play where admission is $20 per ticket. As you

enter the theater you discover that you have lost the ticket. The seat was not marked and the ticket cannot be recovered. Would you pay $20 for another ticket?

• Imagine that you have decided to see a play where admission is $20 per ticket. As you

enter the theater you discover that you have lost a $20 bill. Would you still pay $20 for a ticket to the play?

• Imagine that you have decided to see a play where admission is $20 per ticket. As you enter the theater you discover that you have lost the ticket. The seat was not marked and the ticket cannot be recovered. Would you pay $20 for another ticket? [No: 54%]

• Imagine that you have decided to see a play where admission is $20 per ticket. As you enter the theater you discover that you have lost a $20 bill. Would you still pay $20 for a ticket to the play? [Yes: 88%]

• But in both problems, the final outcome is the same if you buy the ticket: you have the same amount of money and you see the play. Why should these cases differ?

Dependence on Ratios (Tversky and Kahneman, 1981)

• Imagine that you are about to purchase a jacket for $250, and a calculator for $30. The calculator salesman informs you that the calculator [jacket] you wish to buy is on sale for $20 [$240] at the other branch of the store, located 20 minutes drive away. Would you make the trip to the other store?

• Results:

- 68% willing to make extra trip for $30 calculator

- 29% willing to make extra trip for $250 jacket

• Note: save same amount in both cases: $10. Why the discrepency?

Neoclassical Assumptions About Preferences

• The chosen option in a decision problem should remain the same even if the surface description of the problem changes (descriptive invariance)

- Contradicted by pseudo-certainty and framing effects

• The chosen option should depend only on the

outcomes that will obtain after the decision is made, not on differences between those outcomes and

- the status quo: Contradicted by endowment effect

- what one expects: Contradicted by mental accounts

- the overall magnitude of the decision: Contradicted by ratio effect

More Neoclassical Assumptions About Preferences

• Preferences over future options should not depend on the transient emotional state of the decision maker at the time of the choice (state independence)

Endowment Effect Revisited (Van Boven, Dunning, and Loewenstein, 2000)

Replicated coffee mug endowment effect

- Avg. selling price: $6.37

- Avg. buying price: $1.85

• Sellers [Buyers] asked to estimate how much buyers [sellers] would pay, and rewarded for accurate predictions

- Sellers' estimate of buying price: $3.93

- Buyers' estimate of selling price: $4.39

• Result shows "projection bias": estimates are biased toward Ps emotional state at the time of estimate (attached or unattached to mug)

• Validated for predicting one's own selling price before owning a mug (Loewenstein & Adler, 1995)

Why you shouldn't shop on an empty stomach (Read & Van Leeuwen, 1998)

• Office workers choose between healthy and unhealthy snacks to be received in a week

• Decision times and projected snack reception times either when

- hungry (late in afternoon)

- satiated (right after lunch) • Results: % choosing

unhealthy snack:

Future

Hunger

Hungry Satiated

Current Hungry 78% 42%

Hunger

Satiated 56% 26%

More Neoclassical Assumptions About Preferences

• Preferences over future options should not depend on the transient emotional state of the decision maker at the time of the choice (state independence)

- Contradicted by projection bias

More Neoclassical Assumptions About

• Preferences over future options should not depend on the transient emotional state of the decision maker at the time of the choice (state independence)

- Contradicted by projection bias

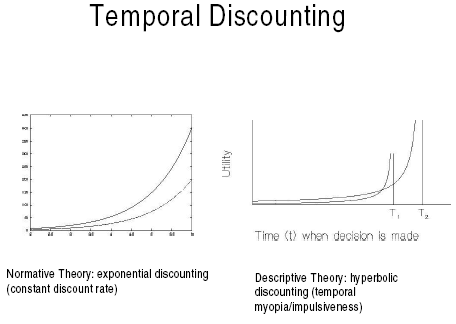

• Preferences between future outcomes should not vary systematically as a function of the time until the outcomes (delay independence)

Testing Delay Independence (Ainslie and Haendel, 1983)

• Ps chose between two prizes to be paid by reputable company:

- 1. $50 today versus $100 in 6 months

- 2. $50 in 12 months versus $100 in 18 months

Testing Delay Independence (Ainslie and Haendel, 1983)

• Ps chose between two prizes to be paid by reputable company:

- 1. $50 today versus $100 in 6 months

- 2. $50 in 12 months versus $100 in 18 months

• Most chose $50 today in problem 1, but $100 in 18 months in problem 2

• Violates delay independence - illustrates hyperbolic discounting

More Neoclassical Assumptions About Preferences

• Preferences over future options should not depend on the transient emotional state of the decision maker at the time of the choice (state independence)

- Contradicted by projection bias

• Preferences between future outcomes should not vary systematically as a function of the time until the outcomes (delay independence)

- Contradicted by hyperbolic discounting/impulsiveness

• Preferences over future options should not depend on the transient emotional state of the decision maker at the time of the choice (state independence)

- Contradicted by projection bias

• Preferences between future outcomes should not vary systematically as a function of the time until the outcomes (delay independence)

- Contradicted by hyperbolic discounting/impulsiveness

• Experienced utility should not differ systematically from

- decision utility

- predicted utility

- retrospective utility

The Harvard/Yale Assistant Professor's Problem (Anecdotal)

• Harvard and Yale grant tenure to very few junior faculty

• But prestige considerations often cause acceptance of job offers over schools more likely to grant tenure (e.g. Michigan)

• Result can be a miserable experience: drop in status, feeling of failure when assistant professorship is over

• Possibly an instance of decision utility (revealed by choice) being inconsistent with experienced (and even predicted) utility

• Anticipated by Adam Smith: people exaggerate importance of social status

Failures of Hedonic Prediction

• People neglect effects of adaptation to surroundings in predicting future utility

- Misprediction, after initial (unpleasant) exposure, of (non) enjoyment of plain yogurt after 8 daily episodes of consumption (Kahneman & Snell, 1992)

- Change in social comparison group (e.g. teaching at Harvard/Yale, moving to a new neighborhood)

- Weariness with travel - planning overly long vacations, too much time at the beach

• Assistant professors overestimate effects of tenure decision on happiness one year later (Gilbert and Wilson, 2000)

A Test of Hedonic Memory (Kahneman et al., 1993)

• Ps given two unpleasant experiences:

- Short trial: Hold hand in 14°C water for 60s

- Long trial: Hold hand in water for 90s; 14°C for 60s, followed by gradual rise to 15°C over next 30s

• After second trial, Ps called in to repeat one of the two trials exactly

- 65% chose to repeat the long trial

• Interpretation: "duration neglect" - people remember and overweight the end of the experience (a gradual decline in pain)

Application in Clinical Setting (Redelmeier and Kahneman, 1996)

• Patients undergoing colonoscopy reported intensity of pain every 60s

• Later provided several measures of remembered utility for the whole experience

• Remembered utility ratings reflected not total utility (addition of pain ratings) but a "peak and end" rule: highest and last pain ratings dominated memory

• Failure to integrate moment utilities: may account for difference in reported happiness between French and U.S. survey-takers

More Neoclassical Assumptions About Preferences

• Preferences over future options should not depend on the transient emotional state of the decision maker at the time of the choice (state independence)

- Contradicted by projection bias

• Preferences between future outcomes should not vary systematically as a function of the time until the outcomes (delay independence)

- Contradicted by impulsiveness

• Experienced utility should not differ systematically from

- decision utility: Harvard/Yale junior faculty problem

- predicted utility: Contradicted by failure to predict adaptation

- retrospective utility: Contradicted by duration neglect and failure to integrate moment utilities

Prospect Theory (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979; 1992)

Prospects are evaluated according to a value function that exhibits

- reference dependence (subjectively oriented around a zero point, defining gains and losses)

- diminishing sensitivity to differences as one moves away from the reference point

- loss aversion: steeper for losses than for gains

Prospect Theory (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979; 1992)

• Prospects are evaluated according to a value function that exhibits

- reference dependence (subjectively oriented around a zero point, defining gains and losses)

- diminishing sensitivity to differences as one moves away from the reference point

- loss aversion: steeper for losses than for gains

• Probabilities are transformed by a weighting function that exhibits diminished sensitivity to probability differences as one moves from either certainty (1.0) or impossibility (0.0) toward the middle of the probability scale (0.5)

- Refinement of reflection effect: risk aversion for medium-to-high

probability gains and low probability losses; risk seeking for medium to high probability losses and low probability gains

Some everyday, observed consequences of prospect theory (Camerer, 2000)

• Loss aversion:

- Equity premium in stock market: stock returns too high relative to bond returns

- Cab drivers quit around daily income target instead of "making hay while sun shines"

- Most employees do not switch out of default health/benefit plans

- People at quarter-based schools prefer quarters, at semester-based schools prefer semesters

• Reflection effect:

- Horse racing: favorites underbet, longshots overbet (overweight low probability loss); switch to longshots at end of the day

- People hold losing stocks too long, sell winners too early

- Customers buy overpriced "phone wire" insurance (overweight low probability loss)

- Lottery ticket sales go up as top prize rises (overweight low probability win)

More serious consequences

• Loss aversion makes individuals/societies unwilling to switch to healthier living (fear loss of income, unsustainable luxuries)

• Risk seeking for likely losses can cause prolonged pursuit of doomed policies, e.g. wars that are not likely to be won, choosing court trial instead of bargaining

• Risk seeking for unlikely gains can lead to excessive gambling in individuals, quixotic policies when leaders get too powerful

Okay, people are rational and don't have stable preferences, but aren't they at least basically selfish ?

Self-Interest Assumption in Game Theory

• Choices in games should always reflect what is best for the decision maker, i.e. what will maximize the decision maker's payoff

Prisoner's Dilemma Labeling Experiment (Ross and Samuels, 1993)

• When PD is labeled the "Wall Street Game", only 1/3 cooperate

• When it is labeled the "Community Game", 2/3 cooperate

• Shows presence of both tendencies - defection and cooperation - which can be evoked by social signals

The Ultimatum Game (Guth et al.,1982)

• $100 in one dollar bills available to be divided

between two players

• "Proposer" chooses a division

• "Receiver" can either

- accept: both receive proposed amounts

- reject: both receive nothing

• How much should the Proposer offer?

The Ultimatum Game (Guth et al.,1982)

• $10 in one dollar bills available to be divided between two players

• "Proposer" chooses a division

• "Receiver" can either

- accept: both receive proposed amounts reject: both receive nothing

• How much should the Proposer offer?

Ultimatum game experiment (Thaler,1988)

• Most proposers offer $5 (even split), or a little less, to the receiver

- altruism

• Low offers ($1) usually rejected

- "altruistic punishment"

Dictator Game (Kahneman et al., 1986)

• One P (student in class) asked to divide $20 between self and other P. Other P has no choice to accept/reject.

• Two possibilities:

- Even split ($10 each)

- Uneven split ($18 for self, $2 for other)

• Game theory predicts uneven split

• 76% chose an even split

Ultimatum and Dictator Games in Traditional Societies (Henrich et al.,2001)

• Ps tested 15 small-scale societies

• Ultimatum game:

- Mean offer varied from 0.26 to 0.58 (0.44 in industrial societies)

- Rejection rate also quite varied: low offers rarely rejected in some groups, in others high offers are often rejected

• Great variation in behavior even among nearby groups; depends on deep aspects of culture, experience:

- e.g. meat-sharing Ache (Paraguay) and village-minded Orma (Kenya) made generous offers, family-focused Machiguenga (Peru) showed low cooperation

• General conclusion: there is no such thing as homo

economicus; cooperation behavior is highly variable, heavily determined by cultural norms

Effects of a Norm of Self-Interest

• People describe involvement in social cause as being more self-interest motivated than it is (Miller, 1999)

• Voting behavior in U.S. becoming more self-interest- driven (McCarty, in press), may reflect shift toward greater norm of self-interest in politics

• Economic theories and language "can become self- fulfilling" (Ferraro, Pfeffer, and Sutton, 2003)

Finally...

• Cognitive psychology can inform many areas of research, theory, and practice that do not now properly incorporate its insights

• Theories about psychology, whether grounded in data or not, can have profound consequences for the way we live

No comments:

Post a Comment